The likelihood is that things will get worse before they get better. The shelves may still be full, but the damage is already underway. Tariff wars and isolationist policies are hitting small businesses hard, and many expect rising prices and shortages to follow. Like Joseph, we see the trouble ahead, and prepare not to hoard, but to share. Like Jesus, we choose to show up where it hurts. The Church must be ready, at the protest line and at the pantry.

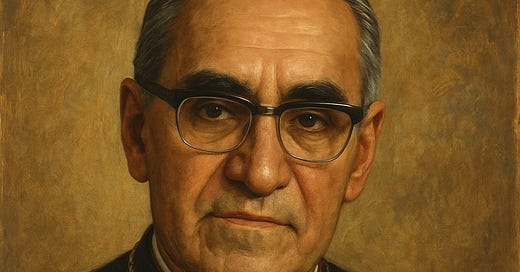

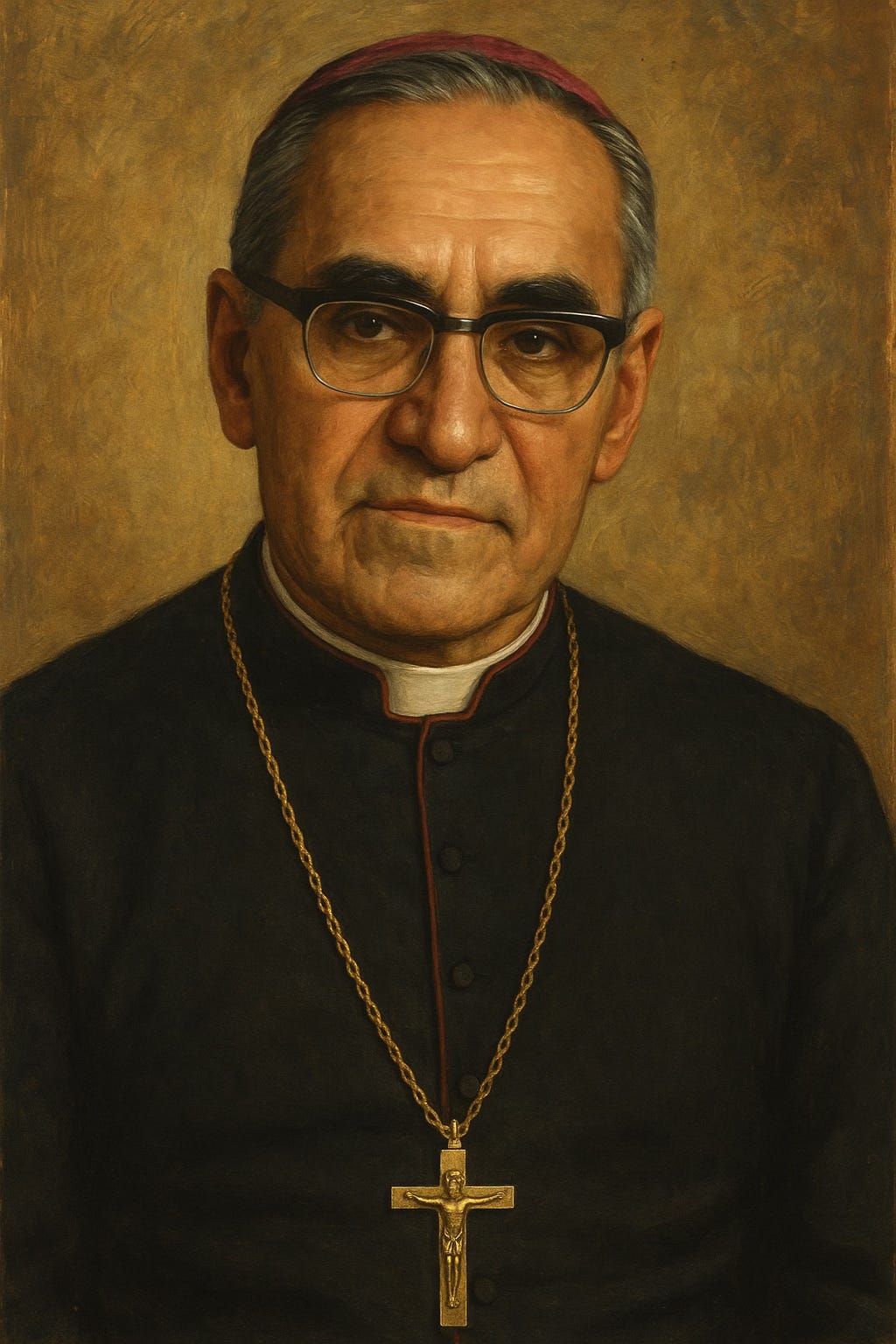

In these times, we need not only clarity to name and unmask the Powers at work in our nation, as I’ve explored in recent posts, but also fresh courage to resist dehumanization faithfully. Fear is contagious, but so is faith. One way we cultivate that courage is by walking in the footsteps of those who have gone before us. Óscar Romero is one such witness who continues to inspire me.

On March 24, 1980, while lifting the bread of the Eucharist in a small chapel at the Hospital de la Divina Providencia, Archbishop Óscar Romero died as a martyr of his faith by an assassin’s bullet, for naming the Powers and standing with the poor. His death was not the end, but a seed. “If they kill me,” he had said days earlier, “I will rise again in the people of El Salvador.”

Romero’s witness has become global. A statue in his likeness stands at Westminster Abbey’s Great West Door in London with ten other martyrs, positioned between Martin Luther King Jr. and Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Each a faithful resister who gave their lives confronting systems of injustice. Romero’s impact reached far beyond El Salvador. He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979, received honorary doctorates from Georgetown and Louvain, and in 2010, the United Nations named March 24 the International Day for the Right to the Truth concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims.

But Romero’s journey to his witness for Christ was neither linear nor predictable.

He was born in 1917 in Ciudad Barrios, a small village in El Salvador. His childhood was poor but marked by deep devotion. At 13, he entered a Catholic high school for those discerning the priesthood and later studied theology in Rome. He was disciplined, meticulous, and a traditional conservative who upheld the established order, serving as secretary of the San Miguel diocese for twenty-three years. He held a powerful role, and as editor-in-chief of the diocesan newspaper, his influence and persona were communicated to the public.

For much of his early ministry, Romero was seen as cautious and somewhat timid, focused on personal piety, wary of political entanglements, and even suspicious of aspects of the growing liberation movements within the Latin American Church, which he sometimes publicly criticized. His appointment as bishop of the Diocese of Santiago de María, a poor, rural region, reconnected him with the people. As he moved from his scribal roles into the pastoral demands of the episcopacy, this began a transformation in his life and thinking.

Romero’s appointment as Archbishop of San Salvador in 1977 was influenced by the oligarchy and the government, who saw him as a “safe” choice. Those oppressed by the prevailing social structures feared the worst. But both groups misjudged him.

Just eighteen days after his installation, Romero’s close friend and fellow priest, Father Rutilio Grande, was ambushed and killed by government forces, along with two parishioners: 72-year-old Manuel Solórzano and 16-year-old Nelson Lemus. Grande had been organizing Christian base communities and defending the rights of the rural poor. He was too effective, too threatening to the status quo. His death marked a decisive turning point for Romero: not a conversion from unbelief to belief, but from a reductionist faith to a robust embodiment of Jesus and his kingdom. He moved from being cautious and reserved to becoming a bold voice of love and justice.

For Grande’s funeral, Romero held a single public Mass for the entire archdiocese, against the objections of some of his fellow bishops, and refused to attend any state functions blessing the new president-elect until a full investigation into the murders was conducted. Some bishops, who benefited from close ties to the government, criticized Romero for politicizing the Church by refusing to attend the inauguration. Romero replied, “Since when has the archbishop’s presence at a presidential inauguration not been a political act?” For him, there could be no peace without justice.

Romero increasingly stood publicly with the poor and oppressed, transforming the institutional Church into a platform for truth-telling. Each Sunday, his homilies were broadcast across the country, so widely listened to that they often surpassed football (soccer) in popularity. It was said you could walk through any Salvadoran town and not miss a word of his message, as radios blared from windows and cars. This was likely because, after his sermons, Romero would name the kidnappings, tortures, disappearances, and executions carried out by the regime and its paramilitary allies. His solidarity with those discarded by the government would not allow him to remain silent, even when Rome urged a more cautious posture.

Romero’s faithfulness wasn’t born of ideology. He consistently warned against placing hope in either leftist revolutions or right-wing control. He was not beholden to party or platform. His allegiance was to Jesus and his kingdom. In one homily he warned:

“Let us not put our trust in earthly liberation movements. Yes, they are providential, but only if they do not forget that all the liberating force in the world comes from Christ.” – Romero, The Violence of Love, p. 140

Romero embraced what I call in The Scandal of Leadership a kenotic spirituality, a self-emptying, self-giving faith, rooted in the kenosis of Christ found in Philippians 2. He did not use his office to secure comfort or favor. He lived in a simple room beside the hospital where he was later assassinated. He rejected offers of luxury homes and expensive cars. He poured himself out daily for the sake of the people. His homilies were laced with both truth and grace. While he gave preference to the poor and oppressed, he always extended love to all, even those who were torturing his own people.

“For when Christ corrected those of his time, he did not hate them. He loved them… that they might seek the true way where they can find the mercy God offers.” – Romero, The Violence of Love, p. 57

Romero’s theological vision grew as he engaged the writings of Vatican II and the liberation theology of the Latin American bishops at Medellín. He came to see the church as the Body of Christ in history, not above or apart from the suffering of the people, but immersed in their struggle.

When the church hears the cry of the oppressed it cannot but denounce the social structures that give rise to and perpetuate the misery from which the cry arises. – Romero, Voice of the Voiceless, loc. 1835

This was not theology as abstraction. It cost him dearly. Under Romero’s leadership, six priests were assassinated. Many religious leaders were tortured or deported. And yet, he did not flinch.

When the church ceases to let her strength rest on the power from above – which Christ promised her and which he gave her on that day – and when the church leans rather on the weak forces of the power or wealth of this earth, then the church ceases to be newsworthy. The church will be fair to see, perennially young, attractive in every age, as long as she is faithful to the Spirit that floods her as she reflects that Spirit…” – Romero, The Violence of Love, pp. 48–49

Romero did not seek martyrdom. But he was not under any illusion. His life had become a threat to those in power. He knew death was near:

I was told this week that something was being plotted against my life. I trust in the Lord, and know that the ways of providence protect one who tries to serve him. – Romero, The Violence of Love, p. 116

And yet, he did not stop. On March 23, 1980, in his final Sunday homily, he issued his most direct appeal yet, speaking to the military who were present at the service:

“No soldier is obliged to obey an order contrary to the law of God.

It is time you obey your consciences rather than sinful commands.

In the name of God, in the name of this suffering people,

I beg you, I implore you, I order you: Stop the repression!”- Quoted in Michael Lee’s, Revolutionary Saint, p. 141

The next day, he was killed at the altar. His blood soaked the floor beside the table of the Lord. But his voice did not die. It still echoes.

Just two weeks before his assassination, Romero gave a final interview to El Independiente, one of the only newspapers not controlled by the oligarchy. He said:

“I have frequently been threatened with death.

I must say that, as a Christian, I do not believe in death but in the resurrection.

If they kill me, I will rise again in the people of El Salvador.

I am not boasting; I say it with the greatest humility.

As a pastor, I am bound by a divine command

to give my life for those whom I love,

and that includes all Salvadorans, even those who are going to kill me.

If they manage to carry out their threats,

I shall be offering my blood for the redemption and resurrection of El Salvador.

Martyrdom is a grace from God that I do not believe I have earned.

But if God accepts the sacrifice of my life,

then may my blood be the seed of liberty,

and a sign of the hope that will soon become a reality.

May my death, if it is accepted by God,

be for the liberation of my people,

and as a witness of hope in what is to come.

You can tell them, if they succeed in killing me,

that I pardon them, and I bless those who may carry out the killing.

But I wish that they could realize that they are wasting their time.

A bishop will die, but the church of God—the people—will never die.”– From A Theologian’s View by Jon Sobrino, p. 56

Romero stands as a faithful witness to the reign of God under authoritarian rule. His life reminds us that following Jesus in contested times means refusing the lures of ideology, naming and unmasking the powers, letting go of the status and security the world offers, standing with those scapegoated by the regime, and walking in revolutionary obedience, even unto death.

May his witness guide us today. To learn more about Óscar Romero, check out this lecture from biographer Michael Lee, Revolutionary Faith, Óscar Romero as a Model for Christianity Today.

A Prayer for Courageous Faith

God of the Crucified and Risen Christ,

We remember your servant Óscar Romero,

who stood at the altar and did not flinch,

who lifted the bread and gave his life,

who spoke truth to power with grace in his voice

and love in his eyes.

In a world still ruled by violence and lies,

where the Powers seduce, silence, and scapegoat,

grant us the clarity to name them

and the courage to resist them.

Form in us a faith that is not safe,

but surrendered

a faith that sides with the poor,

speaks truth in public,

and breaks bread in hope

even when the shadows gather.

Like Romero, may we empty ourselves

not in despair, but in defiant love.

May we listen for your voice

in the cries of the oppressed.

May we follow your Son

on the road of the cross,

trusting that resurrection is near.

And when fear tempts us to be silent,

fill us with the Spirit who makes all things new.

We ask this in the name of Jesus,

the Lamb who was slain

and who lives forever.

Amen.

Looking Ahead

As we look to what lies ahead, I sense an invitation into a season shaped by prophetic imagination, the formation of alternative communities, and a Spirit-led movement of hope. This path will be woven with faithful presence on the frontlines, contemplative resistance rooted in love, and the deep promise of eschatological hope. The landscape may shift as the world around us trembles, but the calling does not change: to walk in the Way of Jesus with courage, humility, and trust—whatever may come.

Not just history, but a call to holy defiance today.

Not just a martyr’s story, but a summons to courageous faith.

Not just past witness, but present obedience in the Way of Jesus.